CLOSE

About Elements

田中贵金属是贵金属领域的翘楚企业。

支撑社会发展的先进素材和解决方案、

创造了这些的开发故事、技术人员们的心声、以及经营理念和愿景——

Elements是以“探求贵金属的极致”为标语,

为促进实现更加美好的社会和富饶的地球未来传播洞察的网络媒体。

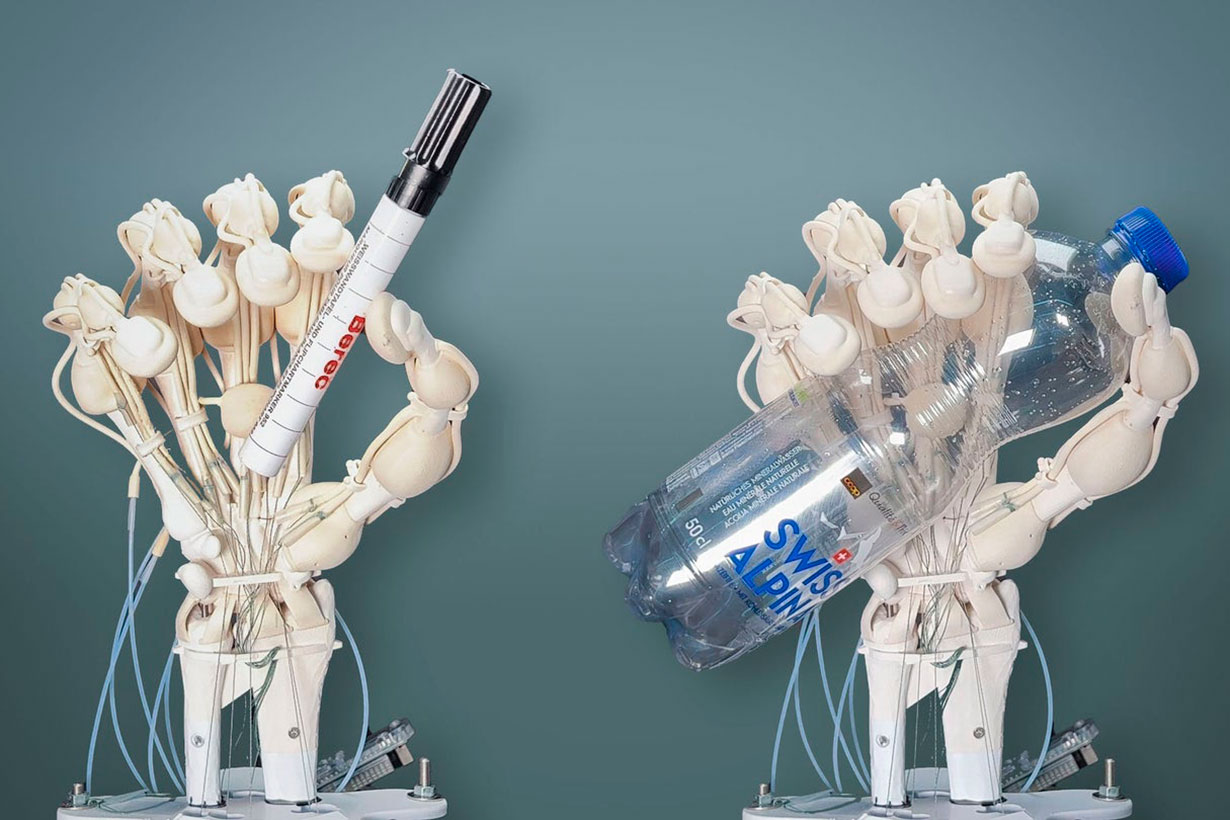

This 3D-printed soft robotic hand has ‘bones,’ ‘ligaments,’ and ‘tendons’

Researchers 3D-printed a robotic hand, a six-legged robot, a ‘heart’ pump, and a metamaterial cube. Top Image Credit: ETH Zurich / Thomas Buchner

To call soft robotic hands “complex” is a bit of an understatement. These designs consider a number of engineering factors, including the elasticity and durability of materials. This usually entails separate 3D-printing processes for each component, often with multiple plastics and polymers. Now, however, engineers working together from ETH Zurich and the MIT spin-off company, Inkbit, can create extremely intricate products with a 3D-printer utilizing a laser scanner and feedback learning. The researchers’ impressive results already include a six-legged gripper robot, an artificial “heart” pump, sturdy metamaterials, as well as an articulating soft robotic hand complete with artificial tendons, ligaments, and bones.

[Related: Watch a robot hand only use its ‘skin’ to feel and grab objects.]

Traditional 3D-printers use fast-curing polyacrylate plastics. In this process, UV lamps quickly harden a malleable plastic gel as it is layered via the printer nozzle, while a scraping tool removes surface imperfections along the way. While effective, the rapid solidification can limit a product’s form, function, and flexibility. But trying to swap out the fast-curing plastic for slow-curing polymers like epoxies and thiolenes mucks up the machinery, meaning many soft robotic components require separate manufacturing methods.

Knowing this, designers wondered if adding scanning technology alongside rapid printing adjustments could solve the slow-curing hurdle. As detailed in their new paper published in Nature, their new system not only offers a solution, but demonstrates 3D-printed, slow-curing polymers’ potential across a number of designs.

Instead of scraping away imperfections layer-by-layer, three-dimensional scanning offers near-instantaneous information on surface irregularities. This data is sent to the printer’s feedback mechanism, which then adjusts the necessary material amount “in real time and with pinpoint accuracy,” Wojciech Matusik, an electrical engineering and computer science professor at MIT and study co-author, said in a recent project profile from ETH Zurich.

To demonstrate their new method’s potential, researchers created a quartet of diverse 3D-printed projects using soft-curing polymers—a resilient metamaterial cube, a heart-like fluid pump capable of transporting “liquids” through its system, a six-legged robot topped with a sensor-informed two-pronged gripper, as well an articulating hand capable of grasping objects using embedded sensor pads.

While refinements to production methods, polymers’ chemical compositions, and lifespan are still needed, the team believes the comparatively fast and adaptable 3D-printing method could one day lead to a host of novel industrial, architectural, and robotic designs. Soft robots, for example, offer less risk of injury when working alongside humans, and can handle fragile goods better than their standard, metal robot counterparts. Already, however, the existing advances have produced designs once impossible for 3D printers.

This article was written by Andrew Paul from Popular Science and was legally licensed through the DiveMarketplace by Industry Dive. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@industrydive.com.